Background

Surviving documents relating to the parklands date from the mid-sixteenth century. By 1670, Rooke Hall, later renamed Upton House, was the main house dominating the area.

In 1762, physician and botanist Dr. John Fothergill bought the house (see here for details), enlarged the grounds, built extensive greenhouses, and planted them with rare and exotic botanical species from around the world.

|

| Dr John Fothergill |

Unfortunately, 260 years later, the Corporation of London has decided to tear down the last of the greenhouses and cover the area with housing.

Fothergill’s botanical gardens were second only to Kew in importance in England. He recorded the details of his plants in records that survive in the British library and commissioned paintings and drawings, many of Catherine the Great of Russia acquired on his death. They languish, untended, in a small botanical museum on the outskirts of St Petersburg.

Although the greenhouses have gone and the paintings are inaccessible, at least one of Fothergill’s specimens remains in the park—the Gingko Biloba tree (pictured), which he is believed to have planted there in 1763.

|

| Fothergill's Gingko Biloba tree |

Upton House was renamed Ham House in the 1780s and eventually acquired by Quaker banker and philanthropist Samuel Gurney in 1812 (see here for details), where he resided for the rest of his life. When he retired from banking in the 1840s, he dedicated his efforts to philanthropy and local land acquisition, and in a piecemeal fashion, he purchased over 30% of the land that is now recognised as Forest Gate.

|

| Samuel Gurney |

Gurney’s older sister, prison reformer Elizabeth Fry’s (see here for details) household fell on hard times in the 1820s. Samuel allowed them to live in a house named the Cedars on the edge of his landholding from 1829 until 1844. That house later became a Territorial Army barracks and local headquarters.

.jpg) |

| Elizabeth Fry |

Soon after Gurney died in 1856, his own immediate family faced financial difficulties following the collapse of the bank he once led. His grandson, John, set about disposing of some of the land Gurney had accumulated, which in many ways led to the growth of Forest Gate as the Victorian commuter suburb it largely remains today.

|

| Ham House in its grounds, before demolition in 1872 |

John Gurney was keen that the 77 acres of his grandfather’s immediate estate should become a public park. He valued it at £25,000 and offered to sell it at half its valuation if local people contributed the other half towards its sale price. A fund was launched to find the money, led by one-time Gurney employee and administrator Gustav Pagenstecher (see here for details).

|

| Gustav Pagenstecher |

The then local authority was unwilling to contribute, and only £2,500 was raised from immediate local sources. Pagenstecher turned his fundraising attention to the Corporation of London, which was already interested in acquiring Epping Forest, including Wanstead Flats, for public use (see here for details).

The Friend, a Quaker publication dated 1 April 1873, explains the Corporation’s interest. It noted, “No parish in London has expanded more rapidly than West Ham. It has seen an increase in population of more than 60% over the last 10 years.”

Gurney and Pagenstecher feared that developers would have bought the land and turned it into housing if it had not become a public park.

The Corporation contributed £10,000 towards purchasing the Park, which was to be open to the public “in perpetuity … at its own expense” from its opening in July 1874. The corporation has run and managed it ever since. Pagenstecher maintained a keen interest and was deputy chairman of its board of trustees from its establishment as a park until he died in 1916. He wrote the first history of the park.

Elements of the history of the park

One of the first things the Corporation did during the acquisition was demolishing Ham House and leaving some of its remnants as a cairn near the park’s main entrance (see photo).

| ||

| Ham House, before its demolition in 1872 | |

|

| The cairn near the main entrance to the park, all that remains of the house today |

The park has many fine features today, including a delightful ornamental garden, children’s play area, bandstands, a café, and pitches and greens for many sports. It is a Grade 11 listed park.

It has often attracted large attendances for special events. The Godwin school diary of 10 September 1895, for example, noted: “The attendance (at school) was good this morning, but owing to the visit of the Lord Mayor and Corporation to West Ham Park, it was greatly affected in the afternoon.”

|

| Entrance to the park, 1907 |

|

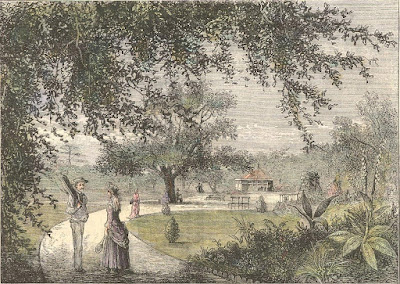

| An Edwardian postcard of the formally laid out park |

Another significant turnout was recorded for the Civil Defence Ceremony of Remembrance on 26 September 1943 – see photo below.

|

| Civil Defence ceremony in the park, 1943 |

Sport has always featured prominently in the park, and Pagenstecher ensured it was well catered for, as indicated in his memoirs:

I’ve always been an enthusiast for cricket. On the Park Management Committee, I used to endeavour to ensure that portions of the Park should be laid out as cricket pitches. I was secretary of Upton Park Cricket Club which dates back as far as 1854 (ed: i.e. some 20 years before the land was formally adopted as public parkland).

Football

West Ham Park is perhaps better known for its unusual football heritage. From 1866, eight years before the grounds were formally designated a park, it hosted Upton Park FC, a club with a couple of unique achievements. It was one of the fifteen clubs competing for the inaugural FA Cup trophy in 1871 and has the distinction of hosting the competition’s first-ever goal, when Upton Park went 1-0 down in the 11th minute of the game (eventually losing 3-1) to Clapham Rovers, on 11 November that year.

|

| Crest of Upton Park FC |

As we approach the 2024 Paris Olympics, Upton Park’s second great claim to football fame comes into view. The club represented GB in the 1900 Paris Olympics and emerged victorious gold medal winners! There is no GB team at this year’s Olympics, so Upton Park’s record as victorious UK footballing Olympians in Paris cannot be matched this summer.

|

| Logo of 2nd Olympiad - Paris 1900 |

The local area has boasted the strange quirk of having Upton Park FC playing at West Ham Park, while West Ham FC played at Upton Park!

What a hotbed of football this small area of Forest Gate was at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries. Just a couple hundred yards from West Ham Park is the Old Spotted Dog ground, home to Clapton FC, who boast several impressive achievements. In 1890, they became the first English football team to play in Europe (beating a Belgian X1 7-0) and competed in six (winning five) FA Amateur Cup finals between 1903 and 1928.