Mark Gorman continues his series on pre-suburban farms in Forest Gate and district (first episode here) by looking at the inhabitants and conditions in Irish Row during the 19th century. In doing so, he updates and elaborates on an earlier feature we ran on the area (here). The detailed story below is a testimony to the dire conditions and poverty endured by local agricultural workers 150 years ago.

Where was "Irish Row"?

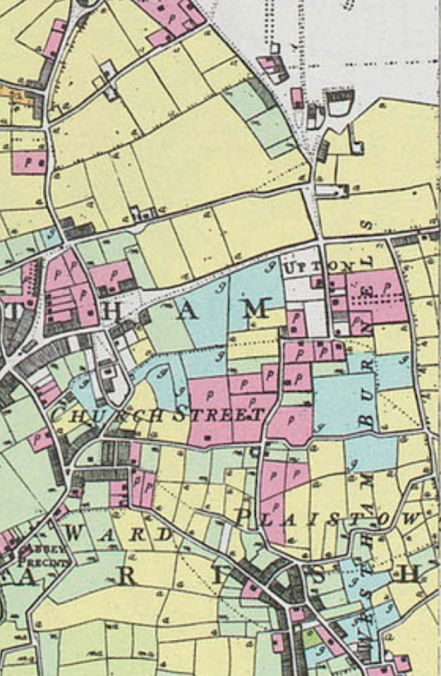

The exact location of Irish Row is elusive. It seems most likely that the name was attached to a group of buildings on what is now the corner of Romford Road, Balmoral Road and Katherine Road in Forest Gate. Irish Row has also been assumed to be the name given to a group of cottages on the north side of Romford Road, the site of which became stables in the late 19th century and is occupied today by a monumental mason. However, the evidence is far from clear. "Irish Row" appears in newspaper reports, census returns and official records, but seems to have been applied in different ways to the buildings grouped together around the junction of the road from Stratford to Ilford and Plashet Lane (sometimes called Red Post Lane) which is today's Katherine Road, stretching to Gipsy Lane (Green Street today).

The cottages on the north side of present-day Romford Road appear as “Ebor Cottages” on the contemporary OS maps. These were sold in 1845 as 8 brick-built cottages “with good gardens in front of the High road”, part of the Greenhill estate (which also included Woodgrange Farm). Ebor Cottages appear (in an 1864 notebook recording the perambulation of West Ham parish boundaries) as Farey’s Cottages, although Samuel Farey, a local surveyor, who lived in The Grove at Stratford, may only have owned one or two, perhaps bought in the 1845 sale.

The 1865 OS 25" map shows only two of the "Ebor Cottages" in existence at that time, but this cannot be correct, as other OS maps of the same period show more houses on this site. (Ordnance Survey revisions did not always keep up with the rapidly changing local geography).

The 1841 census does not clarify the Irish Row question. Its entries for the houses south of the road to Romford appear to be working from west to east, but begin with William Maxwell, the farmer who was a tenant of Plashet Hall and Farm, which would suggest that the enumerator was working the other way! It then lists dwellings called "Irish Row Ramsden's Cottages" (possibly after Joseph Ramsden, a farmer in the small village of Plashet to the south who may have been the leaseholder - he certainly was the tenant of a field south of Romford road). The next group of houses is listed as "Irish Row", the "Upper Irish Row Ramsden's Cottages", after which come Sun Row and Sun Buildings. The list confusingly ends with Plashet Hall, the recorded occupant of which, William Streatfield, lived in the hamlet of Plashet, half a mile south. It is possible that the census enumerator was not working methodically, and loosely applying local names to dwellings.

By the 1860's a terrace and pub or beer-house (the "King Harry") had been built along Plashet Lane called King Harry Row. These were said to abut Irish Row and Sun Row, which stretched along Romford Road. In the 1861 census Sun Row is divided into an eastern and western section, with a group of cottages (Prospect Cottages, which still exists today) and a larger building called Prospect House in between. Another cluster of buildings, Orchard Place, also appears, and in 1891 an Orchard Alley is listed, as is "Sun Row Buildings" which in 1892 were described as being at the back of Sun Row. A discussion at a meeting of the local Board of Health in that year seems to indicate that it was well known that tenements crowded in behind those facing the main road had existed for half a century or more (Barking, East Ham etc Advertiser, 20 February 1892).

So Irish Row as almost certainly a group of tenements between Plashet Lane and Gipsy Lane. Probably the most reliable records of its location are the tithe apportionment map and entries of 1838. These list Sun Row and Prospect Row as two lines of "tenements under one roof" between Plashet Lane and Gipsy Lane. This suggests that the term "Row" was applied to a terrace of houses, in which case Irish Row would have had to be on the south side of Romford Road, since Ebor/Farey's Cottages on the north side were clearly individual dwellings.

All this may reflect the fact that this group of tenements in multiple occupancy was very difficult to define, and defeated the best attempts of officialdom to clarify who was living where. Irish Row may have been a name applied both to a specific group of dwellings and a generic name for a rural slum which occupied this corner for most of the 19th century.

"Irish Row" and its inhabitants

Origins

These tenements existed over most of the 19th century; they were first occupied in the early 1800s, and were still in use in the early 1890s. Although relatively little evidence survives of the lives of those who lived in Irish Row and the surrounding tenements throughout the 19th century the six censuses taken between 1841 and 1891 give some idea of their lives, as do occasional reports in the press.

That Irish migrants were the early occupiers is demonstrated by the 1841 census. Of the 48 household heads 29 were Irish born, as were 18 of their wives. They seem to have been a relatively settled community; of the 112 children living there 105 were locally born, with just 5 being born in Ireland. The ages of the children indicate that 14 families had lived locally since at least 1830, with 8 having probably arrived before the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Ten years later only 11 out of 37 household heads were Irish born, and more than half of these had already arrived in south-west Essex by the late 1830s. None of the 128 children in the 1851 census were born in Ireland, indicating that at least in this small farming community there had been very few incomers as a result of the Irish famine. In 1861 just 6 out of 52 household heads were Irish born, and all of these were long-term residents in the area. This pattern continues through until the last census (1891) before the demolition of the tenements, with evidence of very few arrivals. In the 1850s for example there may have been about half a dozen migrants, judging by the ages of their locally born children in the 1871 census.

Nevertheless, connections with Ireland seem to have been maintained; Irish surnames appear even among those who were born and grew up locally and the 1871 census lists one couple where Forest Gate-born Cornelius Hays had married Catherine Chidle in Ireland in 1856. Since she was born in Cork and the marriage took place in Cashel, Tipperary, it seems likely that Cornelius had his own family connections in Ireland. James and David Barry, both in their forties and both Irish born, lived with their families at 6 and 7 Orchard Place. All their children were born in East Ham, and their ages indicate that James and David (possibly brothers) had arrived in the 1850s. James’ wife Johanna was born in Ireland, but David’s wife Anne was from East Ham. Perhaps one brother had paved the way to East Ham for the other. James Barry’s household included an Irish-born widower, also called James Barry, who was perhaps a cousin. From 1841 onwards a number of households contained Irish-born relatives (ageing parents as well as members of extended families) and lodgers.

Over the half century from 1841 to 1891 the number and proportion of locally-born household heads remained fairly constant at about half of the total. Incomers were predominantly from the south-east of England with a handful of Londoners. Irish Row must have been enlivened by the presence of the well over 100 children recorded in each census until 1881, and there were still over 50 children in 1891, when the number of households had fallen to 31.

|

| Two out of the three Prospect Cottages in 2023. They stood between the terraces of Sun Row East and West. |

Employment

For much of its existence, Irish Row was occupied by farm labourers and their families. In 1841 nearly 70% (33 of 48) of the households were headed by an agricultural worker, rising to 78% (32 of 41) in 1851, and peaking at 80% (42 of 52) by 1861. Thereafter the percentage fell to a still substantial 69% (41 of 59) in 1871, but then declined dramatically to 6% (4 of 66) in 1881 and 12% in 1891 (4 of 31). The 1850s may have been the best years for the inhabitants of Irish Row. Not only were most male household heads working on local farms, a few of their wives (6 out of 50) were also farm workers, while others were orange sellers, a dressmaker, a “small shopkeeper” and a housekeeper. In fact the census may not give an accurate picture of the true involvement of whole families in farm labour; for instance on William Adams’ Plashet Hall Farm, where many Irish Row inhabitants were employed, families worked in groups on pulling, cleaning and bunching vegetables for market. (Essex Herald, 24 Jan 1865).

Between 1841 and 1891 the number and range of occupations other than agriculture rose significantly, though manual labourers were still the predominant group in the 1880s. As we have seen, farm work had however declined significantly by this time. Over the period the number of artisans, shopkeepers and factory workers rose gradually and by the 1880s a wide range of occupations were listed. In 1851 Prospect House on the Romford Road was a tambour lace factory staffed by girls from St George’s parish in Southwark, presumably farmed out by the parish to earn a living. Tambour lace was a method of decorating net by using a tambour hook and a frame. It was an Essex cottage industry centred on Coggeshall, and it is not clear what lace work the girls at Prospect House were doing. The trade was at its peak about 1850, but then declined as fashions changed and machine production came in. By 1861 the tambour lace makers were gone from Prospect House. Behind King Harry Row was an “animal charcoal” factory, where for over two decades the bones of slaughtered horses were boiled down to produce fertiliser and other by-products, providing employment for some living in the tenements.

Living conditions

Throughout their existence these dwellings were barely fit for habitation. A graphic - if prejudiced - description of a visit to Irish Row about the year 1810 is in a memoir of the Quaker philanthropist Elizabeth Fry, who lived in the hamlet of Plashet, to the south of Romford Road (Cresswell, F: A Memoir of Elizabeth Fry (1886) pp 43-44):

"About half a mile from Plashet, on the road between Stratford and Ilford, the passer-by will find two long row of houses, with one larger one in the centre, if possible more dingy than the rest. At that time they were both squalid and dirty. Windows stuffed with old rags, or pasted over with brown paper, and the few remaining panes of glass refusing to perform their intended office from the accumulated dust of years; puddles of thick black water before the doors; children without shoes or stocking; mothers, whose matted locks escaped from remnants of caps which looked as though they could never have been white; pigs, on terms of most comfortable familiarity with the family; poultry, sharing the children's potatoes - all bespoke an Irish colony."

Little changed over the succeeding decades. Looking back over half a century in the early 1890s the chairman of the East Ham Local Board of Health recalled that in the 1840s-50s: "they have ten to twelve in a room ... there were two of them that had as many as fifty or sixty in the house at night. They used to take them in a penny-a-night". Even allowing for exaggeration, this seems to fit with the general pattern of occupation of these tenements. The census returns show many houses subdivided, with numerous "boarders" and relatives sharing accommodation, which was probably common practice locally. In a case heard at Ilford Petty Sessions in 1829 an unemployed Irish labourer declared that when he took in lodgers at the house he rented in Barking, they slept in the same room as his wife and family.

In 1853 the Essex Standard named Irish Row among a number of localities in West Ham where open sewers and cesspools were breeding grounds for disease, warned of the advent of cholera if no action were taken, and called for the establishment of a Local Board of Health. The following year there was a serious outbreak of cholera in West Ham.

Ten years later cases of typhus fever were reported in one house in Ebor Cottages, and the report noted that it had been endemic here and across the road in Sun Row for years. Although typhus is an animal-born disease, the prevalence here was ascribed to open sewers near the houses, about which the now-established Local Board of Health had done nothing. The houses, noted the report, were occupied by poor Irish families. In 1867 The Inspector of Nuisances finally served a notice on the landlord Samuel Farey to drain the cesspool and lay water on Ebor Cottages, but four years on the problem persisted, despite Farey's assurances that he had addressed them.

In February 1871 an inquest was held over the death of Mary Ann Bailey, who lived with her bricklayer husband James in King Harry Row, a line of tenements which stretched down what was then called Plashet Lane (now Katherine Road). Reports of the inquest gave graphic descriptions of the conditions in which the family lived, showing that nothing had changed since Elizabeth Fry’s time.

“The house was one of a row of miserable hovels, abutting on Irish Row. Dark, low pitched, and mouldy rooms, bare of almost any furniture and exhibiting traces on every hand of the greatest poverty. In this den were crowded ten little children, five of whom had belonged to the deceased, and five belonged to a lodger. The hungry-looking little things were but half clothed, and the whole abode wore an aspect of misery”. (Essex Times 25 Feb 1871).

Landlords and tenants

These tenements were owned by several landlords. By the 1860s the biggest landlords were the Oldaker family, who owned properties throughout East Ham and Ilford, and Stephen Carey, who owned the whole of King Harry Row, which consisted of 20 tenements, each of four rooms with gardens behind. There was also a pub, the King Harry. When the tenements were sold in 1876 they were yielding £220 a year in rent, with the pub providing another £25.

Another group of smaller-scale landlords typically had three properties each, possibly bought from the Oldakers as investments for a small income. In the late 1860s, for example, three owners each had three of the Sun Row tenements, charging £4 10s rent a year. At least two of these owners may have been widows. Meanwhile as we have seen Samuel Farey owned at least two of the cottages on the north side of the Romford road, bought in the sale of Woodgrange Farm in 1845, for which he was charging an annual rent of £6 10s.

|

| Carey’s factory was sold in 1876, but the business continued for a number of years. This advertisement is from 1888. |

In addition to King Harry Row, Stephen Carey also owned the “animal charcoal factory”, a knacker’s yard where horse bones were boiled down, located behind King Harry Row and Sun Row. The factory produced fertiliser or “chemical manure” for local farms and a number of the tenants in Sun Row worked there. Carey obviously took his business seriously, having taken out patents on improved apparatus for “reburning animal charcoal” in the 1860s. Nevertheless some idea of the local impact of this factory may be had from the advertisement when it was sold in 1876, describing the property as “just outside the radius within which obnoxious businesses are prohibited”. A complaint about the “horse boiling” works was made to the East Ham Board of Health in 1878, and though it was stated that the nuisance had been removed the factory was still located there ten years later.

It is also notable that on the other side of Plashet Lane from King Harry Row was Plashet Hall (Potato Hall) the home of various large-scale tenant farmers during the nineteenth century. In the 1860s-70s William Adams and later his son, also William, had the tenancy of Plashet Hall Farm. In the early 1860s William senior employed more than 100 farm-workers, most of whom probably lived in the slums grouped around the corner of Plashet Lane and Romford Road. The Adams family would have looked out over the Irish Row tenements from their front windows.

The last years of Irish Row

Right up until their demolition the tenements clustered around Plashet Lane were in a wretched condition. In February 1892 the East Ham Board of Health heard from its “Outdoor Committee” about their inspection of Sun Row Buildings, which appeared to have been cottages at the rear of Sun Row itself, and may have been converted from wash-houses. The committee found the cottages “in a dilapidated state, and the w-c very damp from defective roof and flushing apparatus, and the approach to the cottage very dirty”. They recommended serving notice on the owners to make repairs. The landlord, J.W. Oldaker, wrote expressing surprise at the Medical Officer’s report, declaring that he would never allow his cottages to become unfit for habitation. In a justification familiar to slum landlords everywhere he then blamed everything on a single female tenant who would not leave despite receiving notice to quit, and was drunk and abusive. Oldaker concluded that the cottages were a bargain at 1s 9d a week.

Nevertheless the Board, having heard that the tenant had been removed to hospital, accepted the report. Some members wanted to go further and condemn the tenements, which were “an eyesore to the parish”, but one, Elias Keys, countered that though they were in bad condition they could be made habitable. Since (according to the 1881 census) Keys’ income came from “house property” this may have been a case of landlords sticking together.

The urbanisation of the area increased rapidly towards the end of the century. By the mid-1890s Sun Row had been demolished, and the “animal charcoal” works was also gone, replaced by a smelting works, which itself was the subject of an inspection by the Board of Health due to its smoke emissions. King Harry Row survived for some time longer, but by 1914 it too had disappeared.

|

| The 1910 Valuation Office Survey, the so-called “Lloyd-George Domesday” survey, showing Ebor Cottages replaced by a row of stables |

The site of Ebor Cottages may still be seen today in Balmoral Road, now a monumental mason’s premises, though the existing buildings were constructed as stables, which would have replaced the cottages. Prospect Cottages on Romford Road, which stood between what may have been two terraces forming Sun Row, also survive today.

Appendix

Sun Row etc in Tithe Apportionment records

|

Date |

Plot number |

Owner |

Occupier |

|

April 1838 |

14 “Sun Field” |

Executors of William Wickham Greenhill |

William Maxwell |

|

April 1838 |

15 “Paddock” |

Now John Inyr Burges Esquire |

George Lord |

|

April 1838 |

16 “Rising Sun Inn & stables” |

Now John Inyr Burges Esquire |

George Lord |

|

April 1838 |

17 “meadow” |

Executors of William Wickham Greenhill |

William Maxwell |

|

April 1838 |

18 “Mansion and garden” (Plashet Hall) |

Executors of William Wickham Greenhill |

William Maxwell |

|

April 1838 |

19 “Homestead” |

Executors of William Wickham Greenhill |

William Maxwell |

|

April 1838 |

20 “Paddock” |

John Dyer |

John Dyer |

|

April 1838 |

21 “Sun Row consisting of 12 tenements under 1 roof with yards” & “Sun Buildings behind the above consisting of 4 tenements under 1 roof with yards”

|

Executors of William Scoffins |

Cornelius Sullivan Daniel Mahony Edward Castle Eleanor Chard George Smith James Broker Jeremiah Driscoll John Mullin Mary Murray Michael Michael Chard Michael Stabbs Richard Westley Sarah Linnard Thomas Deller William Slater |

|

April 1838 |

22 “Orchard” |

John Dyer |

John Dyer |

|

April 1838 |

23 listed as “Irish Row Ramsden’s Cottages”* in 1841 census |

John Dyer |

John Cocks & Joseph Baker |

|

April 1838 |

24 “House & garden” |

John Dyer |

John Dyer |

|

April 1838 |

25 “malthouse” |

John Dyer |

John Dyer |

|

April 1838 |

26 “beer shop & shed” |

John Dyer |

Matthew Guerrier |

|

April 1838 |

27 “Prospect Row consisting of 12 tenements under 1 roof with yards” |

Executors of William Scoffins |

2 Unoccupied David Barry Dennis Kilfray James Cain James Hagan James Mahony John Lequade John Marrow John Ragan Julia Downey Owen Larkins |

|

April 1838 |

28 “2 tenements under 1 roof with gardens” |

Poor of Stepney |

John Owens Simeon Dawson |

|

April 1838 |

29 “Garden” |

Poor of Stepney |

John Owens |

|

April 1838 |

30 “Colville Hall piece” arable |

Poor of Stepney |

Joseph Ramsden* |

|

31 “Paddock” |

John Dyer |

John Dyer |