Local author and regular blog contributor, Mark Gorman, has undertaken extensive research on pre-suburban Forest Gate and surrounding areas. In doing so, he has produced an impressive account of the farms that dominated the locality, their produce, workforces and markets, between the eighteenth and early twentieth centuries.

We will run a series of articles focussing on the history of these farms, whose legacies survive today in the names of roads and geographic areas in and around Forest Gate. In this opening chapter, Mark provides an introduction to farming in the locality. Subsequent, more detailed, articles on some of the farms will appear regularly on this blog over the coming months.

The farms of Wanstead Flats and Forest Gate – introduction

Forest Gate and Wanstead Flats today show very few signs of their rural past, but before the development of the housing which now surround the Flats the area around the open spaces of the common was dotted with fields and farms. Meanwhile modern Forest Gate developed out of a small hamlet surrounded by farms. This past which now seems so remote is in fact surprisingly recent; the last farm-house on the Flats was demolished in 1963 (even though by then it had become a petrol filling station on Aldersbrook Road), and traces of these farms can still be found in the area today.

Over the coming months we will take a look at some of the farms which existed around Wanstead Flats and Forest Gate, focussing particularly on their later history in the 19th century as urbanisation began to spread, first slowly and by the 1870s in a wave which eventually swept away nearly all traces of the area’s rural past. We’ll visit Cann Hall, west of the Flats towards Leytonstone, the two Aldersbrook Farms, Hamfrith Farm and Woodgrange Farm, both south of the Flats in Forest Gate, Plashet Hall Farm on the highway between Stratford and Ilford, and two smaller farms or smallholdings, Druitt’s Farm on Wanstead Flats near the City of London cemetery, and Rabbits Farm on Romford Road.

We’ll go over to East Ham to Jews Farm, an agricultural enterprise which became a local agro-industry over the course of the later 19th century, and played a minor role in the growth of women’s trade unionism. We’ll also take a look at the history of a farmworker community centred around a group of tenements known collectively as “Irish Row” which stood on what is now Romford Road.

Agriculture in the area

From the Anglo-Saxon period, and perhaps even earlier, the southern part of Epping Forest was an area of agricultural production, both through grazing animals and growing crops. Over centuries in the parishes of the southern forest land was cleared and fields formed. Much of the production was for local consumption, but as time went on and London began to grow, the importance of commercial agriculture grew. This part of south-west Essex was close enough to London to be a prime provider of produce for the ever-growing metropolitan market.

Until the late 1600s Londoners' diest were meat and bread based; fruit and vegetables were not widely eaten. It was therefore not until the mid-18th century that market gardens began to be significant in local farming, though potatoes had been a staple crop of the local farmers in the West Ham parish for centuries. The parish was said to be one of the poorest near London. One farmer, writing probaly in the late 17th - early 18th century, complained that although "the planting of Potatoes ... sometimes helps us to pay our REnts and that not once in three years". He believed that the closeness to London actually undermined the local economy.

As London expanded, this began to change. The stimulus of the metropolitan market caused local farmers in both East and West Ham to begin to grow market garden produce on a commercail scale. Already in the 1750s potatoes and turnips were imporatnt local crops. In 1974-5 about 450 acress were sown with potatoes and a further 120 acres with cabbages and other vegetables, representing in all over half the arable area of the parish. Daniel Lysosn described the area and its importance for the London food market in "The Environs of London", published in 1796 -

“In proportion as this great town has increased in population and opulence, the demand for every species of garden luxury has increased also; and, from time to time, fields have in consequence been converted into garden-ground, till a considerable proportion of the land within a few miles of London became occupied for that purpose. The culture of garden-ground is principally confined to those parishes which lie within a moderate distance of the river, on account of the convenience of water-carriage for manure, which, since the prodigious increase of carriages, as well of hackney and stage coaches as of those kept by private families, is procured in great abundance from the London stables”.

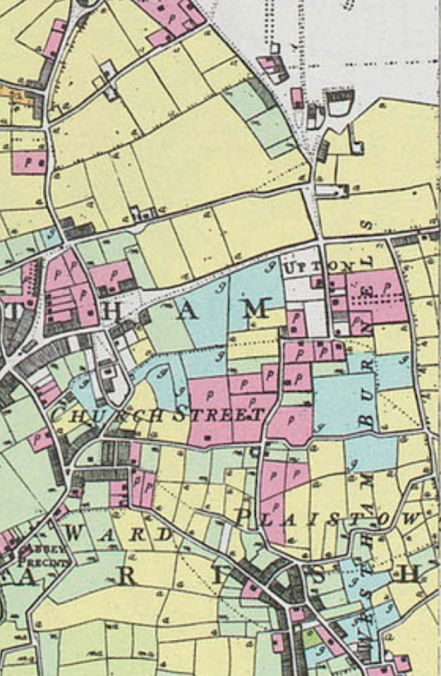

In apparent contradiction of this account Thomas Milne’s Land Use Map of 1800 showed that the area around Forest Gate was still mainly arable, and the Flats were surrounded to the west and south by meadows and fields of grain crops. According to Milne it was only south of the main road to Ilford that market gardens were appearing. Unfortunately his map does not cover East Ham where more market gardens may have been located (see map). Given Lyson’s comments above it is possible that Milne underestimated the extent of local market gardens.

Potatoes and the growth of London

Notwithstanding Milne's map. much evidence points to the increasing emphasis on growing vegetables for the metropolitan market. Three factors played a role in the growth of commercial market gardening locally. Free draining soil, the availability of a ready supply of manure and the proximity of "an insatiable market for produce" were key reasons for the success of commercail vegetable production. Indeed such was the importance of the potato crop on the land around Forest Gate at this time that Plashet Hall, a large mansion built by the Greenhill family on the corner of Plashet Lane (now Katherine Road) and the main road to Romford, became known as Potato Hall, even appearing with this name on an early Ordnance Survey map, and the name survived at least until the 1870s.

|

| Thomas Milne’s Land Use Map (1800): Forest Gate was mainly arable fields (yellow); market gardens (blue) were appearing south of Romford Road. Upton was mainly large houses with parks (pink). |

Athough the Greenhills were pioneers of commercial potato production, after 1800 other local producers were also growing potato crops and sending them into Spitalfields market (the main destination for Essex vegetable crops) for sale. The proximity of the metropolitan market meant that produce could be sent in daily, the carts leaving overnight to arrive at Spitalfields by early morning. The need for the manure meant that the returning carts were loaded at collection points (such as the Truman brewery in Mile End Road) and brought back to be spread on the fields immediately.

The opening of the Eastern Counties Railway in 1838 meant that crops could be moved into London even more quickly and cheaply, but this soon proved to be a double-edged sword for local market gardens As a commentator in the 1850s pointed out, "distant counties now compete with all these gardens and gardeners, being able to do so by the railway facilities. Peas, asparagus, new potatoes are thus brought, to the advantage of the London consumers, if not of the suburban growers." Indeed, when the Great Eastern railway (successor company to the Eastern Counties) opened a wholesale fruit and vegetable market in Stratford in October 1879 the dealers who set up there were all from East Anglia, with none locally based.

In the 1840s local potato crops were affected by the same disease as in Ireland, but unlike the Irish situation potato blight locally did not impact on the profitability of local farming. With the huge metropolitan market on their doorstep farmers were able to adapt to both growing conditions and market demand by diversifying into other vegetable crops. When blight struck the potato crop at Woodgrange Farm in the 1840s the whole crop was sold at a heavy loss, but this was recouped when the land was ploughed and replanted with cabbages. From the early years of the century the high quality of the "Imperial East Ham Cabbage" variety meant that it was sold by seedsmen across the country. Local growers sold cabbages into the London markets in large quantities. Peas and onions were also grown extensively.

Farmers and their workers

Until the mid-19th century farming in the Forest gate area was a profitable business. Most farms were rented by tenants, who made a good living supplying the nearby metropolitan market. A few families farmed in the area over several decades, and names such as Adams, Lake, Greenhill and Circuit reappear consistently. James Adams, who died in 1832, had farmed in Plaistow, and from 1843 his son, William, was the tenant at Woodgrange Farm, which, which tigether with Plashet Hall Farm gave him an estae of over 800 acres and a workforce of 116 men by the early 1860s. The lakes farmed at Cann Hall and Aldersbrook, while the Greenhill family had extensive lands across Forest gate and East Ham, including both Hamfrith and Plashet Hall Farm before the family's finacial difficulties foreced the sale of their properties in the 1830s-40s. Thomas Circuit farmed extensive market gardens in East ham, specialising in onion production, a business eventually taken over by Crosse and Blackwell.

The scale of these operations is illustrated by a description of William Adams' business in the 1860s. On his 850-acre Plashet Hall Farm he was employing 116 workers, with an annual wage bill of over £6,000. Adams' total outgoings, including wages, rent, rates and tithes, commissions to salesmen in the metropolitan wholesale markets and contracts to buy manure from large-scale stables, cowhouses and breweries in London amounted to £20,000 annually (well over £1 million today).

Adams was farming on an industrial scale, Each year production per acre was up to 70 tons of cabbages and greens, 12 to 20 tons of carrots and 8 to 12 tons of potatoes, followed by 10 to 14 tons of onions, and then by a further cropping of greens and cabbages. "As soon as one crop is off another is put in; the only respite is in the winter time, before the onion crop, when it is left bare for season frost. The land is being perpetaully robbed."

This intensity of cropping could only be sustained by abundant application of manure. 80 tons of dung per acre was a normal dressing, and the soil was drained and deep ploughed to enable the huge quanity of manure to work into the roots of the plants. The smell which must have hung over the area throughout the year can only be imagined. William Adams was also an innovator; like his neighbour Chamberlayne Hickman Lake at Cann Hall he experimented with steam ploughs. "The land about East Ham lies in large and open fields, and is admirably adapted for steam cultivation; and Mr Adams is on the point of introducing the steam plough. It will be almost the first introduction of it into the business of growing vegetables for the London market, to which it is nevertheless perfectly adapted". The Gardeners Chronicle could only describe these operations in industrial terms - "We do not suppose that there is a larger manufactory of food for London anywhere."

The first migrant workers

Potato growing also attracted the arrival of Forest Gate's first group of overseas migrants. By the late 18th century Irish migrants were coming to both East and West Ham to provide labour for potato growing. An estimate of when the first Irish workers and their families arrived is difficult to establish, though Irish migrants were living in the Forest gate area by the early 1780s. We know little of their circumstances, and sources such as vestry minutes and newspaper reports usually focussed only on the crime and disorder which they claimed was associated with Irish migrants. For example, it was reported in 1790 that a large body of men, who said they were Irish, had commited armed assaults in the parish. In 1810 the newspapers reported the sensational murder of John Bolding, the landlord of the eagle and Child after "a large body of Irish labourers" broke into the pub. Six were found guilty and three were executed for the crime.

Despite what the newspapers thought, the Irish migrants formed the backbone of local agriculture from the late 1700s onwards. They were employed in numbers by the local farmers; in the 1820s John Greenhill at Hamfrith and Richard Gregory at Woodgrange Farm both had significant Irish workforces. Irish migration seems to have peaked around 1816, in the economic downturn that followed the ending of the Napoleonic Wars, and then again in 1831.

|

| The murder of John Bolding at the Eagle & Child 1810 |

Many of the migrant families were living in poverty, but received little sympathy from the local parishes, who were mainly concerned about the impact on the Poor Rate. A meeting of West Ham vestry in February 1819 heard that numbers of "the poor" had been rapidly increasing in the parish since 1815, particularly during winter months and "that the great increase of the poor are, for the most part, of the Irish labourers, who in the summer season, go to different parts of the County [i.e. Essex] to Harvest Stock, Hop picking &c; and after these works are over, they return into this Parish, and are employed in the Neighbourhood for a few weeks in getting up Potatoes, and upon the finish of that Stock (about the beginning of November) they with their wives and families quarter themselves upon and are mainatined by the Parish until the next Spring and the scarcity of Employment has been such that very few get any Stock to ease the parish of the burthen of the maintenance of themselves and Families, and altho' the Workhouse has been greatly enlarged and improved it is still found very inadequate in size to the increasing number of poor who apply for admission."

Ten years later the vestry noted that the workhouse had over 200 inmates, "and also the out Door poor ... have been much increasing" and warned that the Poor Rate might have to be increased "if some means are not adopted to avoid the burthen of the Irish poor."

In 1833 the neighbouring parish of East Ham was said to be "overwhelmed with Irish poor", who it was claimed made up 3/4 of the local population.

|

| The Poor Rate was paid by all owners and occupiers of property within the parish |

Parliamentary acts in the 18th-early 19th century had given magistrates the power to return Scottish and Irish "vagrants" on application from the local overseers of the poor, and East Ham parish was said to be removing 50-60 "Irish vagrants" daily (a number which seems very high and is probaly greatly exaggerated), at a cost to the parish of £4-5. This was administered under a system of removal orders (known as passes) by which "vagrants" were sent to their home parish with a small cash amount. In 1833 a parliamentary select committee on Irish vagrants reported that the pass system was abused by Irish and Scottish migrants who applied for passes, then simply disappeared to another parish and later returned to claim further poor relief. As a result, another parliamentary act tightened the law, and migrants began to be sent back directly by ship.

Despite these draconian measures, there seem to have been very few cases of repatriation enforced by the local parishes. On occasion the Essex magistrates restrained the zeal of parish authorities to remove migrants, by applying a principle they called "moral settlement", where migrants could prove lengthy residence locally. Such a case was heard at Ilford petty sessions in 1829, when two Irish widows appealed against the attempt of West Ham parish officers to expel them. They said they had lived in the parish for 15 years, where both their husbands died, and had no family connections in Ireland. The magistrate, the redoubtable R.W.Hall Dare, declared that if the women could prove their local residence over 15 years they could claim moral settlement.

It was more common for magistrates to authorise specific cash sums of poor relief for local workers, which due to the seasonal nature of local farm work tended to spike in the winter months. Magistrates were not always sympathetic to claims, declaring profligacy in the summer months was the cause of penury in the winter, and often committing claimants and their families to the workhouse.

Despite the claims of the parish authorities, there is little evidence of large numbers of migrants from Ireland arriving in East or West Ham after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Even the famine years in the 1840s do not seem to have led to a significant increase in migrants locally, although nationally very large numbers arrived, particularly in the peak famine year of 1847. From 1845 the East Ham potato crops were affected by disease, which may help explain why there was not a larger influx of people fleeing famine in Ireland.

"Irish Row"

From their first arrival, many Irish migrants were living in poor conditions, and many families lived in a group of houses collectively named as "Irish Row". This little hamlet clustered around the corner of the road to Ilford and Romford (now Romford Road), on the corner of what was then called Plashet Lane to the south, and is now Katherine Road. The earliest references to these tenements are from about 1811, and they were still in existence in the early 1890s. Occupied for most of this time predominantly by farm workers, Irish Row and its neighbouring tenements formed some of the poorest housing in the area, bringing into question the idea of pre-development Forest Gate as a rural idyll. A more detailed account of Irish Row will feature in a future blog.

Wages and poverty

By the mid 19th century this rural way of life was increasingly impacted by urban development. A lifelong resident of East Ham recalled in the early 1930s that 50 years previously there had been market gardens on both sides of the road from the site of the future East Ham town hall to Manor Park. Yet housebuilding was gathering pace, and from the 1860s some farmers were beginning to relocate from the area.

Local farms needed significant labour to maintain the intensity of their production. It seems that rather than directly paying their whole workforce they employed a contract system, rather like that in operation on the local brickfields. Thus William Adams, whose labour bill varied between £70 a week in winter and nearly £200 a week in spring and summer, paid over the wages to foremen with whom he had contracted. These were either groups of men, working on a share basis, or where women and children were also employed, families could be working together. Probably households in Irish Row were working in this way. Thomas Circuit, who was growing onions for pickling at Jews Farm in East Ham employed 600 men, women and boys in pulling, carting and peeling onions for pickling during the summer months. His wage bill was £2OO weekly (about £12,000 today). Much of this work was done by women who were paid by the rod of ground (approximately 5 metres). During the harvest season Circuit was said to be making about 1500 different payments daily, as his employees received their wages three or four times a day.

Farm worker wages in south-west Essex during the first half of the nineteenth century were probably higher than elsewhere in England. Local farm productivity seems to have been high, and market gardening yielded good profits. A gang of 20 workers on Woodgrange Farm in the 1830s could lift 12-13 tons of potatoes daily, earning 35/- (£1.15p) a week each, equivalent to the earnings of a skilled artisan. A carter on the same farm earned 18/- weekly. Towards the end of the following decade, a carter could be earning 25-28/- a week locally.

However, work was seasonal and insecure, and even during harvest periods was not guaranteed. In 1852 Thomas Circuit refused pea-picking work to a group of “mainly Irish” labourers, as he already had enough hands. This resulted in a violent confrontation and damaged to crops before the police arrived to disperse the crowd. Competition between workers could also be intense. In 1830 Irish and Scottish workers at Woodgrange Farm were in dispute over the Scots’ proposal to plough up potatoes rather than dig them with spades. The confrontation ended with the prosecution of one of the Irishmen for assault.

Some farm workers could provide for themselves from their own gardens or from rented allotments. In 1842 The Gardener’s Chronicle covering the South Essex Horticultural Show

reported that “Upwards of 30 prizes were awarded to Cottagers for fruit and vegetables, mostly grown on the allotments let out by S. Gurney, Esq., Upton: they thus receive a double reward, in the superior quality and abundant crop, and also the value of the prizes-varying in amount from 5s. to nearly 30s, each”. It was also common to allow “gleaning” of fields after a crop had been harvested, a practice which often shaded over into theft of crops.

Thefts from farms

The regular newspaper reports of thefts from local farms, usually involving farm employees, also testify to the difficulty of surviving on wages alone. In the 1830s Richard Gregory of Woodgrange Farm claimed that it was a common practice for farm workers to steal items overnight and store or sell them in local inns (notably the Pigeons on the Romford highway). Twenty years later the thefts were continuing, despite harsh sentences for offenders. In 1853 James Ainsworth, an ostler at the Pigeons was sentenced to transportation for 14 years after being convicted of receiving a large consignment of oats stolen overnight from a barn at Woodgrange Farm. Produce was also stolen from farm waggons as they made their way into London in the early hours of the morning.

|

| The Pigeons pub before 1885, showing farm carts with produce for the London market outside |

Gregory and Adams both alleged that carters taking produce into London would stop at pubs along the way and sell items ranging from farm stock to the oats they had been given to feed their horses. Even manure had a value. In 1871 three workers from Plashet Hall Farm were convicted of stealing dung belonging to their employer at Truman’s brewery, each receiving one month’s hard labour. Gates and even sections of hedges were also taken, and thefts of growing crops were very common, a problem not just for large-scale farmers but also smallholders. As we have seen some claimed that gleaning after harvests was a practice allowed by local farmers, and two “destitute-looking women” caught taking onions from a field in Gipsy Lane got off with a caution. Two months later one of William Adams’ employees was not so fortunate after stealing onions; he received a sentence of two months’ hard labour.

Poverty was undoubtedly a major factor in these thefts, many of which were of small quantities, probably to feed families. During the campaign against the Corn Laws in the 1840s evidence was produced from West Ham that “sober and industrious men” who were being paid the going rate for farm labour locally were only able to feed their families “the very refuse of potatoes, without meat or bread”. Farm workers had little sympathy from employers like Gregory and Adams however. Gregory maintained that his neighbours were afraid to prosecute thieves for fear of having their homes set on fire or animals killed. He blamed the opening of a beer shop in Forest Gate for exacerbating the problem.

Urbanisation and the end of farming

By the mid-19th century this rural way of life was increasingly impacted by urban development. A lifelong resident of East Ham recalled in the early 1930s that 50 years previously there had been market gardens on both sides of the road from the site of the future East Ham town hall to Manor Park. Yet housebuilding was gathering pace, and from the 1860s some local farmers were beginnig to relocate from the area. Between 1861 and 1863 Thomas Circuit left his farm at North End (near East Ham station) moved out to Rainham, In the next few years land round his farm in Jews Farm Lane (now East Avenue E12) was sold for building, although in a sign of the industrialisation of agriculture Crosse and Blackwell maintained Circuit’s picking sheds until the 1890s. William Adams’ son, also William, and his business partner sold up at Plashet Hall Farm and moved out to Dagenham in 1879, and Plashet Hall was never again a solely agricultural enterprise. Also in the 1870s the lands of Woodgrange and Hamfrith were sold for building, as was Cann Hall a decade later.

While many local farms were sold, operations on those that remained were increasingly curtailed. Market gardening continued, though on a much smaller scale than previously.

Census firgures and local directories from the 1840s to the 1860s track the rise and decline of farming locally. Building development came to West Ham parish earlier than East Ham, so farms disappeared here some years before they did in the neighbouring parish. At mid-century, West Ham remained essentially a rural community. It contained 1,100 acres of arable (including market gardens), 2,600 acres of meadow and pasture, 8 acres of woodland, 62 acres of domestic gardnes and orchards and 82 acres of osiers and reeds. By 1905 only 127 acres of arable farmland remained, most of it east of Prince Regent Lane. The last market-garden at Plaistow is said to have closed in 1905, and in the same year the closure of some watercress beds near Temple Mills, suspected of spreading cholera was recommended.

East Ham was to follow this pattern a couple of decades later. In 1839 a local directory records 16 farms in East Ham, of which 5 were over 100 acres. This number remianed the same in 1863 and 7 were described as market gardens.

Census records of farm labourers tell a similar story. The number of male agricultural workers in East Ham rose from 266 in the 1841 census to 360 ten years later. By the early 1860s though, numbers had declined to 166, reflecting the decline of agriculture as urban development gathered pace.

|

| Beddall's Farm, Newham's last working farm, in East Ham, Manor way, Beckton. Picture from 1970s, some years after the farm's closure. |

However, of the farms around Forest Gate, only Aldersbrook dairy herd could claim to retain any resemblance to a working farm after 1918. Over the course of no more than half a century a way of life that had existed since the first settlements of East and West Ham had disappeared.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We welcome comments to all the items featured on this site. However, we reserve the right to omit offensive comments, and edit the length of comments, for reasons of space.